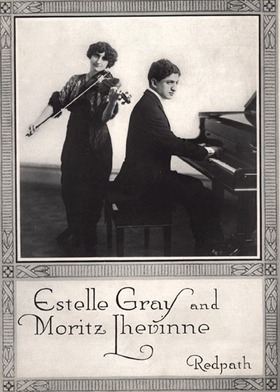

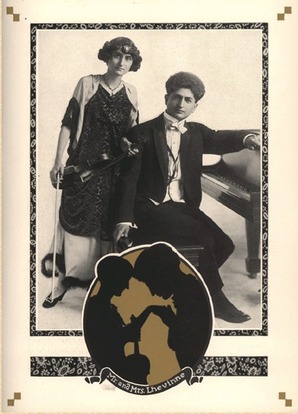

But soon there was trouble in paradise. The March 22, 1922 issue of Variety had this short news item: “Too much temperament is the basis of a suit for divorce filed here [San Francisco] by Mrs. Estelle Gray Lhevinne, concert violinist, against Moritz Lhevinne. She accuses him of cruelty and asserts that he was fond of moving the furniture about in the room during the early hours of the morning, and was given to nagging her. In her complaint, she asks the custody of their one child, two and one half years old.” The divorce was granted, presumably with more grounds than a predilection for off-hours interior design on the part of the husband. While a Google search for Mischa Gray-Lhevinne provides lots of information on Misha Dichter, Rosina Lhevinne, and even Mischa Elman, the pianist seems to have disappeared from the media once the duo dissolved their partnership.

Viro "Laddie" Gray-Lhevinne

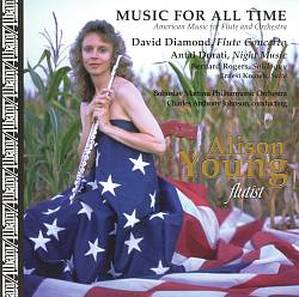

Viro "Laddie" Gray-Lhevinne Laddie Boy Gray Plays as Mozart

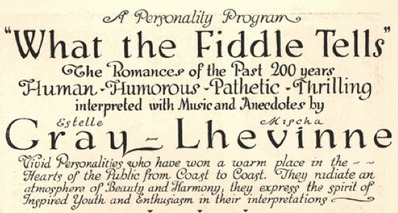

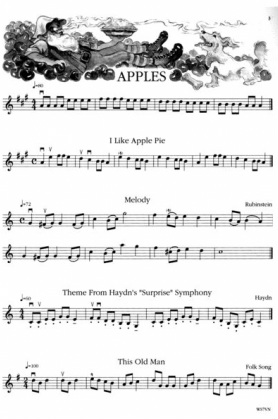

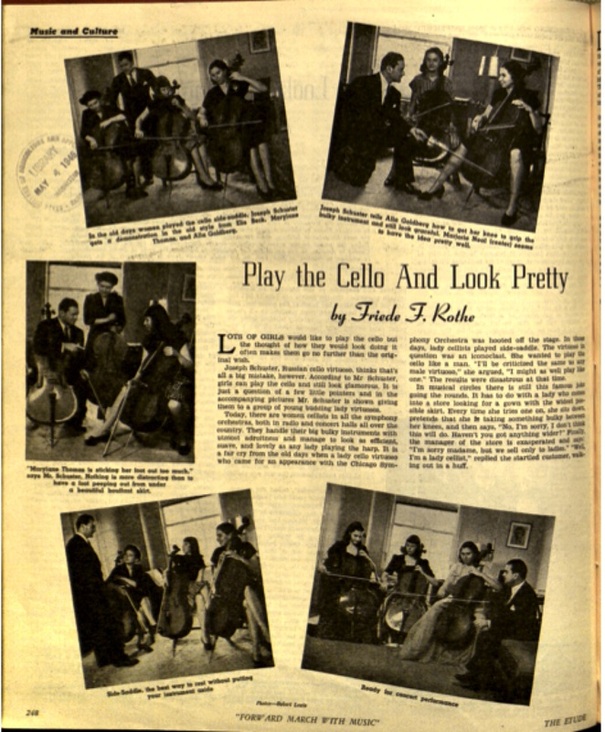

Uniqueness and finish characterizing their program, Laddie Gray, young boy pianist, and Estelle Gray-Lhevinne, violinist, played in assembly, Monday, Dec. 12.

After Mrs. Gray-Lhevinne had played one group of Classical numbers she stated, “Laddie will give his first group of numbers costumed as the boy Mozart. We are not introducing any prodigy, merely showing you a picture of Mozart in his first appearance in court.” The costumed Laddie then played one of that composer’s minuets. He played with a confident touch which produced a very good tone.

His next numbers which he played “as himself” were compositions by Bach, Haydn, and Beethoven. These were all cordially received.

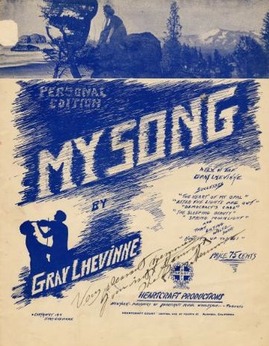

Then, after several more classics, preceded by a story about each, the mother played four pieces of her own composition, reciting the original words before playing them.”

Laddie began performing at age four, and Estelle was quoted as saying that she only allowed him to travel with her a few weeks each year, for his development. “The rest of the time he lives a rustic life in his San Francisco bay home, with earnest diversified studies in advance of the usual boy his age.”

In May, 1933, at the end of a six-week concert tour with Laddie, Estelle needed time to rest before returning to California. She entered a Boston hospital, and sadly and apparently unexpectedly, passed away two days later.

Clearly Estelle Gray brought much joy and music to audiences in her forty or so years of life. I’m glad the internet gave me a chance to know about her.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed