I had found Audrey Call's Canterbury Tales Suite during anthology research, and even though it's in a jazzy style unnatural to me, I wanted to play it. Then I received an email last year asking me if I knew about Susan Dyer's An Outlandish Suite. The fine folks at interlibrary loan found it for me, and I loved how unusual and quirky it was. All I needed was one more piece of Americana to round out the program, so I went back to my roots and brought out a work from volume one, the Kansas Memories Suite by Hannah Bartel (now Hannah Groening). It made for a very light-hearted little recital!

I commissioned this suite from her for the first volume of the anthology. She writes wonderfully for strings, and has a natural gift for melody. Each movement captures a moment from her childhood, and focuses on a different technical aspect of violin playing: string crossings, pizzicato, legato, and perpetual motion. The pieces are not only useful for teaching, but are really fun to play! Below are links to sound files for the first and third movements:

"Rainy Daze"

https://app.box.com/s/jt7bqa8ydihjxpq43obe

" 'Lil Blue"

https://app.box.com/s/tn0crpr1yf2xhzutpnl6

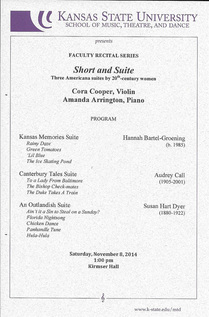

On her return to America, Call got involved in radio broadcast work. She was the violin soloist for the "Fibber McGee and Molly" radio show for several years, and married the show's orchestra conductor, Ulderico Marcelli, in 1937. Call also played on the radio shows of other luminaries of the day, including Dennis Day, Imogene Coca, and Ronald Coleman. She was also a staff violinist for both NBC and CBS. The 1930's also saw her turn her hand to composition. Call wrote a number of "novelty solos" for violin and piano in a jazzy/blusey/big band sort of style popular at the time (The Witch of Harlem is one, which you can find in volume four of the anthology). Her style has been compared to that of Joe Venuti, though I'm not sure how apt that comparison may be.

Call had one son with Marcelli, and the marriage was a long and presumably happy one. She continued to compose and play, and was a dedicated violin teacher in Sunland, California. After her death, a music scholarship was established in her name at Santa Rosa Junior College. Call played a Gagliano violin, which is now owned by the concertmaster of the Cologne Philharmonic, Geoffrey Wharton.

The Canterbury Tales Suite is in three movements, each of which seems to present a character from the stories. Full disclosure-- I've never read the book so I am guessing at the correspondences based on an internet synopsis. Sorry! Please correct me if you know better. The first movement, "To a Lady from Baltimore," I'm guessing to be related to the Wife of Bath, a fun-loving, risqué, scarlet-dress-wearing woman of five marriages. The music is seductive, interrupted in the second part by a march and a sinister take on "Here Comes the Bride." Call makes use of whole-tone scales (perhaps a French influence?), upbow staccato, glissandi, and harmonics.

"To a Lady from Baltimore"

https://app.box.com/s/sledq46b1ap5q4xzgyhp

The other two movements, in my humble and uninformed opinion, depict the Friar and the Knight, respectively. The second movement starts with rather furtive music, and later launches into a jazzy, somewhat disguised version of the snake-charmer tune. The Friar was a slime-ball; he dressed like a beggar to get money, pretends he has a lisp for sympathy, calls the poor scum, and carries little presents for pretty girls. I'm stretching terribly for the third movement. The Knight went on many crusades, and the opening sounds like a meandering horse's gait. The piece then launches into stereotypical "Asian" music-- lots of double stop 4ths and 5ths-- indicative of travels in the east. And then somehow it all becomes train music, with "all aboard" glissandi and chugging. Lots of fun!

Dyer moved with her parents to Winter Park, Florida, and taught at Rollins College from 1914-1922 (serving as director of the conservatory from 1916). She resigned from Rollins to become the Director of the Greenwich House Music School Settlement, but sadly died within a few months of taking the post.

Dyer was known for her keen sense of humor, which is readily apparent in An Outlandish Suite. I didn't know what to expect from such a title, but I think it relates to the idea of "outliers"-- people from the fringes of society at that time. The original program notes for the posthumous premiere stated, "Under this title Susan Dyer grouped together some of the musical impressions and reactions of years of travel. Through all her voyages and varied sojourns as a naval officer's daughter, she kept her sharp ears open to whatever music was wafted her way; and this suite is her vivid response to the musical color and emotional temper of races black and red and white and yellow." The first movement, "Ain't it a Sin to Steal on a Sunday," is subtitled "Negro Song." There were many versions of this tune, from "Ain't it Grand to Live a Christian" to "Ain't it a Sin to Beat Your Wife on a Sunday." This version was used as an encore in the 1922 musical Shuffle Along, the first all-black cast Broadway show. Movement two, "Florida Nightsong," bases the piano part on the birdcall of the chuck-will's widow (which you can hear here: http://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Chuck-wills-widow/sounds). This movement was performed and recorded by Heifetz. The unusual third movement is a Seminole ceremonial dance, the chicken dance (no, not the one you do at weddings). The piano part gets more and more insane as it goes along, with Amanda describing it as a "robot chicken on fire," and me to say, "this chick has issues." The "Panhandle Tune" is a cowboy song adapted by Dyer with beautiful simplicity. Lastly, the fifth movement is "Hula-hula," to be played "Not too fast, but with savage rhythm" yet "insinuatingly." The violin has many quick slides meant to suggest steel guitar. This quirky suite is very violinistic in writing and full of surprises!

"Florida Nightsong"

https://app.box.com/s/8rendp3yy1ylkkldcabm

"Chicken Dance"

https://app.box.com/s/miua9l0q34edf361j2cr

RSS Feed

RSS Feed