“A feud between Parisian men and women musicians was reported a few weeks ago by Transradio Press in one of its daily Women Make the News broadcasts... According to this source, the discord is “all due to the fact that women’s orchestras are now so popular (in the French capital) that some of the men musicians are having a tough time getting work in night clubs and cafes. The feud reached such a height recently that 16 police guards had to be called out to quell a riot. They found a young woman violinist holding a crowd of men, and using her violin case as a weapon of defense. The violinist, Estelle Francen, had just arrived at an assembly hall in Montmartre where hopeful musicians gather for bookings. A group of men musicians spied her and an angry shout rang out: ‘There is one of them!’ The men looked so threatening that Miss Francen turned and ran. They pursued her until she sought refuge in a subway entrance. For 20 minutes, she kept the men musicians back as she slashed vigorously with her violin case. The 16 gendarmes arrived just in time to save the girl musician from the angry mob of jobless men musicians.”

The issue of physical appearance, this time with a twist, is used in conjunction with economics in this quote from the December 1938 newsletter:

“Quoted from Musical Leader is an article concerning discrimination against women orchestral players by leading conductors who cannot throw tradition to the winds. But there is something more than tradition that prevents major orchestras from employing women. Lady patrons of symphony concerts are in the large majority. They go to symphony concerts to see an orchestra of men. There would be a big slump in attendance if the orchestra became a mixed affair. A woman’s symphony orchestra is a specific organization. A man’s orchestra should be manned by men, because this is the only way it can be maintained.”

Some of Petrides’s reports show that the prejudice against women in orchestras stemmed from a rather misguided form of chivalry. For example, these two excerpts from July 1937 and January 1938:

[from Wm. J. Henderson, NY music critic] “There is no good reason why women should not be employed in orchestras. The chief question to be asked is whether they can play as well as men. After that, other considerations may be taken up. Can a conductor enforce discipline among the women as well as he can among the men, or will they have recourse to tears when the hard-hearted one addresses the instrumental body in merciless rebuke? Can women endure the severe strain of long and repeated rehearsals?”

[Richard Czerwonky, Musical Observer] “Women orchestra players are not popular with conductors, mainly because the conductors do not feel at liberty to swear as occasion demands before them, as they do before a lot of men. A conductor, in the stress of rehearsal, cannot stop and delete his favorite remarks when things are not going so well, just because there are ladies present... No man who is a gentleman can [swear] without the instinct of apology when there are women around– and that is the main reason why women are not popular as members of symphony orchestras.”

Nevertheless, professional women musicians continued to increase in numbers, though even where accepted, they had a treacherous path to tread. The regard for modesty and beauty had never completely vanished, but presented new pitfalls in the modern era. Again from the Women in Music newsletter, April 1939:

[Paul Denis, Billboard NY editor] “Many are the problems confronting girl musicians in the popular music field. Girl dance band musicians must not smile at patrons, because they, the girls, may be misunderstood. They must not engage in friendly banter with male patrons near the bandstand because the women patrons may suspect that the girl musicians are trying to steal their men. The girl musicians must be dressed attractively but not flashily – so that they will impress as musicians and not as flirts. The leader of the girl band must be careful, too. She must be genial, and more attractive than the rest of the orchestra – but she, too, must be careful not to appear to be flirting with male patrons. Because of this situation, many high class hotels are afraid to book girl dance bands...”

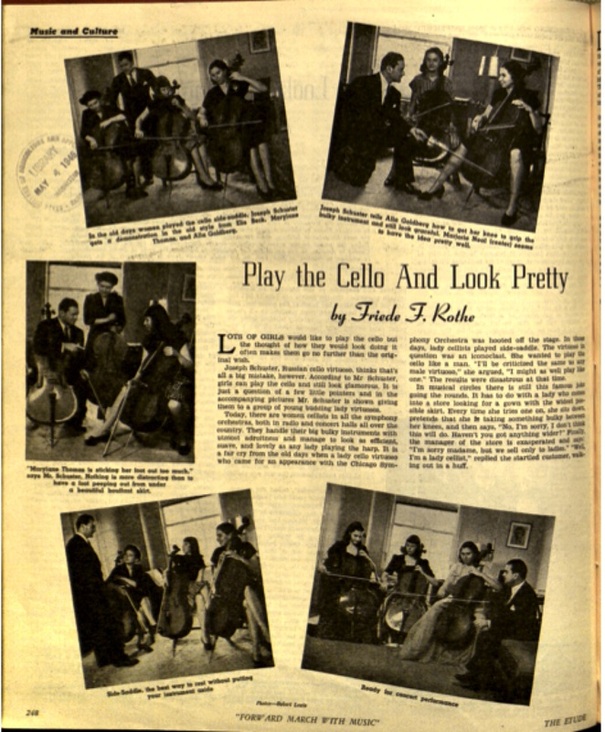

Many articles appeared in the 1940's and 50's that, while appearing to be supportive of women instrumentalists, still reinforced many clichés and placed a disproportionate emphasis on appearance. This image, from the May 1946 issue of Etude Magazine, illustrates this well:

Ha. Ha. Ha.

last installment to come!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed