Professionally, Ms. Richter has had a career marked by honors and successes both in America and abroad. Her work in the 1950’s and 1960’s, notable in itself, also helped pave the way for later women composers such as Ellen Taaffe Zwilich and Joan Tower. She has received grants, awards and commissions from the National Endowment for the Arts, the Martha Baird Rockefeller Fund, the National Federation of Music Clubs, Meet-the-Composer and ASCAP. Her 1964 ballet, Abyss, was commissioned by the Harkness Ballet and performed in most of the major cities of Europe and North and South America during the next few years. It has since been added to the repertoires of the Joffrey and Boston Ballet Companies. Ms. Richter’s compositions have been played by over 45 orchestras throughout the world, including the Minnesota Orchestra, the Milwaukee and Atlanta Symphonies, and the London Philharmonic. She has written of her work, “Visual experiences and nature are the primary inspirations for Marga Richter's music. Sources as varied as the paintings of Georgia O'Keeffe, a New England winter scene and the exotic landscape of Tibet have all served to trigger the composer's creative responses.” Her music has a unique sound, frequently dissonant and always intriguing. You can find much more information, including a works list, at www.margarichter.com.

Richter studied piano with Roslyn Turek, and composition with Vincent Persichetti and William Bergsma at Juilliard, receiving a Master’s Degree in 1951. In a lovely note she sent me dated September 26, 2008, Richter wrote, “I arrived in Manhattan, NEW YORK, 65 years ago today, after a Greyhound bus trip from Robbinsdale, MN. It was a glorious sunny day and like stepping into a whole new world, with mother, brother, dog and Steinway upright in tow!” The whole family relocated so that Marga could pursue her dreams halfway across the country. Her life is now the subject of a full-scale biography by Sharon Mirchandani, published by the University of Illinois Press.

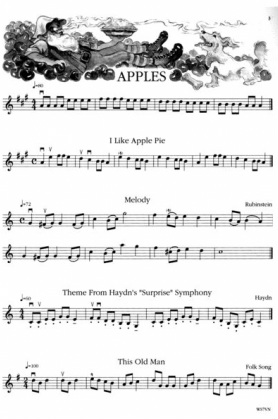

I really wanted to include a piece that would be a great introduction to more contemporary harmonies and mixed meters before the last volume of the anthology. The Three Pieces are largely playable in first and third position, but feature asymmetrical and mixed meters (the first movement mostly alternating 7/8 and 4/4 measures) and dissonance. The violin part is quite fun to play, especially the driving first movement with a somewhat primal eighth-note brush stroke motif. One word of warning—the piano part is very difficult! In particular, the third movement necessitates a slower tempo than the violin part seems to indicate. The pianist is generally twice the speed of the violinist, with a great deal of chromaticism and tricky rhythms.

As a challenge to that brainy kid, and an ear-opening first exposure to “mid-century modern” music, check Marga Richter’s Three Pieces for Violin and Piano. You’ll be glad you did!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed