In the early 20th century, Edith Lynwood Winn (1867-1933), that tireless pedagogue with her many How to Study... books (for Kreutzer, Fiorillo, Rode, and Gavinies) used poems as prefaces to the pieces in her compositions for violin and piano. For instance, the three pieces from From the Carolina Hills included in volume one of the anthology have the following poems:

"A Picture"

My summer’s gone—where did it go?

The land is covered o’er with snow,

The air is sharp upon the hill,

My hands are cold—I feel the chill

Of wintry winds that blow.

And yet I sit and think, and lo!

The pine within the grate doth glow,

While down the misty, snow-clad hill, I catch a song of sweet good-will,

And though the summer’s gone I know

‘Twill come again.

"The Sunshine Lad"

The Sunshine Lad has a morning song,

For all the world like a robin’s note,

Clear and true, joyous and free,

Though the rents are many in cap and coat.

The Sunshine Lad has a basket of pine,

The long-leaved pine of the Old North State,

The song it sings is a sunshine song,

As it sputters and sparkles in the grate.

"Buy My Pine"

“Buy my pine! Buy my pine!

The long-leaved pine—the emerald pine,

The scrubby pine full of turpentine,

For the pine of the hills is mine—all mine.”

A child cried out in the early morn,

A child all dirty and ragged and torn,

And the pine she bore cried back in turn,

“I am thine—all thine, let me quickly burn.”

I haven’t found any attribution for the poems, so my assumption is that they were written by Winn herself. Her use of poems in these pieces, as well as in two other collections (Five Playtime Pieces and Six Shadow Pictures), seem to be to set the mood, or perhaps inspire the mind to loftier considerations. I tried singing the words along to the music, and in every case it was a dismal failure.

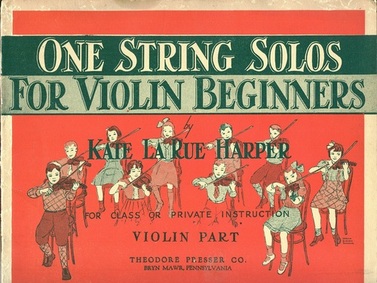

"Kitty Needs a Pill"

Go and call a doctor, Kitty’s very ill.

Ask him if he’ll hurry, Oh I hope he will!

Kitty’s had a spill, Now she’s very ill;

Go and call a doctor, Kitty needs a pill.

And:

"Lazy Little Bug" (D string Solo)

Lazy, lazy, little bug, Lying there asleep

Warm and snug beneath the rug, Wrapped in slumber deep.

When your little nap is o’er, And you stretch your legs once more,

You may find your dream was true, Someone really stepped on you!

Humans also receive their share of trouble (“Bobby cries in bitter woe/Just because he stubbed his toe”). In fairness, not every tune focuses on sickness, pain or death, but enough do that the thought of having a child memorize the words in order to learn the rhythms of the song gives me the heeby-jeebies.

The only other work by La Rue Harper that I've found listed is a one-act juvenile opera called Tomboy Jo’. Tomboy Jo’ is a poor orphan girl who is ostracized by both girls and boys for her gender-inappropriate looks and behavior. Here are the stage directions for her first entrance: “Tomboy Jo’ comes in turning cartwheels, or some other boyish trick. She has short hair and is boyish and unkempt. The boys and girls in chorus exclaim: ’O, here comes Josephine!’ They look at each other as if she were not welcome in either group.” It all comes right in the end when a tramp arrives and turns out to be her long-lost father, who has been stricken with amnesia (and her mother died of a broken heart after he wandered away). Somehow his return allows the others to accept her… I haven’t been able to find any biographical information on La Rue Harper, but I hope her life was more pleasant than all this suggests.

Next, some far happier contributions from contemporary female teachers!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed