“What grieved me was those accursed grills, which allowed only tones to go through and concealed the angels of loveliness of whom they were worthy. I talked of nothing else. One day I was speaking of it at M. le Blond’s. ‘If you are so curious,’ he said to me, ‘to see these little girls, I can easily satisfy you. I am one of the administrators of the house, and I invite you to take a snack with them.’ I did not leave him in peace until he had kept his promise. When going into the room that contained these coveted beauties, I felt a tremor of love such as I had never experienced before. M. le Blond introduced me to one after another of those famous singers whose voices and names were all that were known to me. ‘Come, Sophie’-- she was horrible. ‘Come, Cattina’-- she was blind in one eye. ‘Come, Bettina’-- the smallpox had disfigured her, Scarcely one was without some considerable blemish. The inhuman wretch le Blond laughed at my bitter surprise. Two or three, however, looked tolerable; they sang only in the choruses. I was desolate...”

Clearly Rousseau anticipated a high level of physical beauty to correspond with the higher level of musicianship found in the soloists. To be fair, he does end this passage with a slight change of heart: “Ugliness does not exclude charms, and I found some in them. I said to myself that one cannot sing thus without soul; they have that. Finally, my way of looking at them changed so much that I left nearly in love with all these ugly girls.”

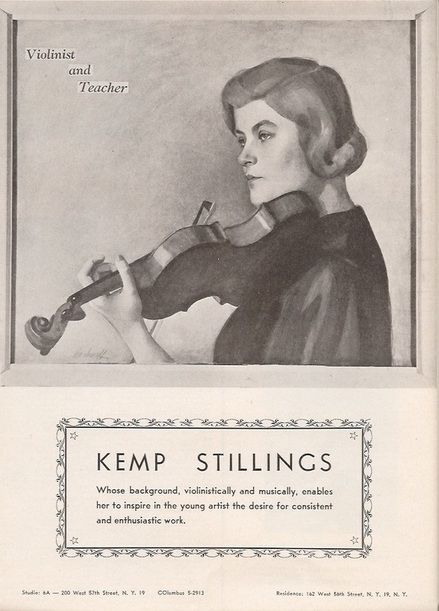

The students of the ospedali were, for the most part, orphans or illegitimate children. Being of a lower social class excused them from the prohibition against playing instruments considered disfiguring (such as the violin) or immodest (such as the cello). To quote again from Unsung: “the accepted instruments for girls were those that could be played in a demure seated position, that is, the keyboard instruments (not including the organ, whose pedals required an ungainly posture)... Efforts to learn the violin or flute were frowned on as unsuitable, as late as the 1870's...” While modesty was often given as the reason to keep women from these instruments, the effect on their appearance was sure to draw comment. For example, an 1878 Worchester Evening Gazette reviewer of a concert by the Eichberg Violin Quartet said, “A violin seems an awkward instrument for a woman, whose well-formed chin was designed by nature for other purposes than to pinch down this instrument into position. Nevertheless, we cheerfully bear witness that four bright damsels in a row, all a-bowing with tuneful precision, is an interesting and even a pretty sight.”

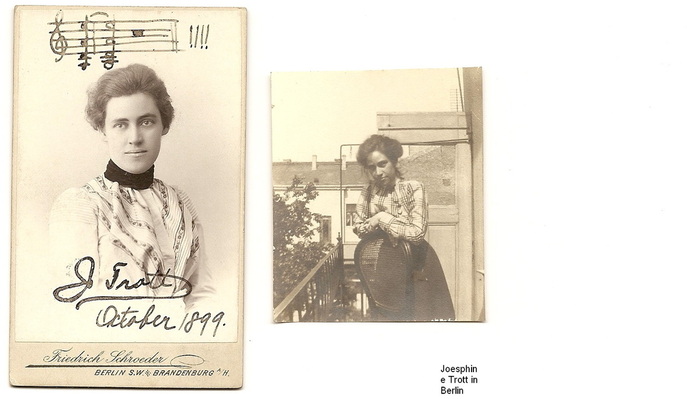

As the damage to our chins became less of a distraction and public performance less of a stigma, new issues arose. The late 19th and early 20th centuries seem to have been a time of transition in the reasons used against women in music. “Appearance,” previously defined as “looks,” could now be defined as “existence.” The central issue became the effect of female musicians on the men around them. They were thought to lower the quality of music-making, as well as distract the men. This was (and sadly still can be) part of the prejudice against women orchestral musicians. Ernst Rudorff, the deputy director of the Berlin Hochschule made his case to his superior, Joseph Joachim, in 1881:

“I would like to ask you to consider seriously whether it is right for us to allow women to take part in orchestra classes and performances. They add nothing to the performances; indeed, I am more and more convinced by the last few rehearsals that the weak and uncertain playing of the young girls not only does no good at all but actually makes the sound indistinct and out of tune... It is bad enough that women are meddling in every possible place where they don’t belong; they have already taken over in almost every area of music. At the very least, we have to make sure that orchestras will not have men and women playing together in the future. It is possible that the general currents are heading in that direction and in the coming decades we may see the last bit of disciplined behavior and artistic seriousness driven out of public productions of pure instrumental music. In any case, I would not like it to be said that an institution like the Royal Hochschule has taken the lead in entering upon this path towards immorality. Thus I propose that in the new year... the participation of women in orchestra classes and performances come to an end, once and for all. If I had to add anything to this, I would go one step further and exclude the women from auditing the orchestra classes as well. With only a very few exceptions, they do nothing but exchange looks with the men and chatter.”

More Catch-22's. While Herr Rudorff complained about the level of ability among the women students, he strove to deny them the opportunity to improve their skills! Two developments in the late 19th century helped to circumvent this particular argument. First, exceptional violin soloists of the time, such as Camilla Urso and Maud Powell, disproved the notion that women were incapable of great artistic achievement. Second, the all-female orchestras such as the Boston Fadette Lady’s Orchestra, led by Caroline B. Nichols, began to provide necessary training, and career opportunities as well. Interviewed by the Pittsburgh Gazette Times in 1908, Ms. Nichols commented, “The field for women musicians is growing... Why, when the Fadettes began to appear for professional engagements, people looked askance, and the men musicians smiled and said wait until the public hears them. Well, the public did hear them, and the public liked them so much that we’ve never had an open week from that day to this that was not of our own making.”

Uh oh. Now women were definitely having an effect on the male musicians around them, and it was one that really hurt. They became an economic threat.

more to come...

RSS Feed

RSS Feed