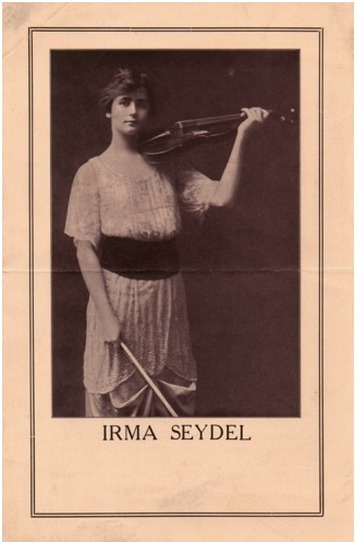

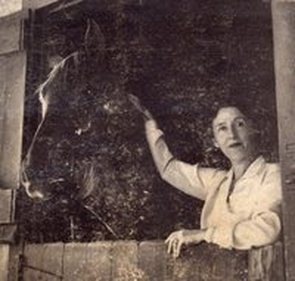

I have to admit to a certain fascination with the early 20th century. The clothes! The changing times! All things Downton Abbey! And of course, the professional female violinists breaking new ground in their era. Irma Seydel (1896-?) was one of those young women, achieving virtuoso status and making her way as a concert soloist at least into the 1920's.

Seydel was helped along by having a father in the Boston Symphony, who started her on the violin at the age of three. She studied with the renowned violinist, composer, and teacher Charles Martin Loeffler from the age of ten, and later on made the obligatory "finishing" trip to study in Europe (though I have not discovered with whom she studied). Seydel clearly progressed rapidly, and in 1909, at the age of 13, she was soloist with the Gurzenich Orchestra in Cologne. During her career, she was to perform with the Berlin, Leipzig, and Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra. In America she appeared with the New York Philharmonic, the Chicago, San Francisco, Philadelphia and Baltimore Symphonies, and multiple times with the Boston Symphony.

Seydel often performed the Saint-Saens B minor Concerto, including its premiere performance with the San Francisco Symphony in 1913. The reviewer for that concert wrote, "The youthful virtuoso has spirit, vigor and sympathy. She plays with faultless Intonation and exhibits a rare capacity for expression. She was recalled for two encores, playing Schumann's immortal 'Traumerei' exquisitely."

Seydel also made appearances drumming up business for the Edison Musical Instrument Company. An ad in the May 12, 1918 Reading (PA) Eagle, the Metropolitan Phonograph Company announced a concert at the Rajah Theater in which Seydel, Marie Morrisey (contralto with the Metropolitan opera), and cellist Jack Glockner would "sing and play with and without the Edison, for the purpose of comparison-- see if you discern one from the other." Seydel recorded Kreisler's Liebeslied on an Edison wax cylinder, and later two 78 records (Beethoven Minuet in G and D'Ambrosia Canzonetta). Syracuse University has made an mp3 of the Kreisler recording available here. I love technology! You can hear that, like Kreisler, she uses an almost continuous vibrato. Her approach to rubato and slides are quite conservative for the time. The recording is dated as from 1924.

Seydel married in 1921, an event which seems to have been undertaken in haste. A notice in the March 26 Musical America is headlined, "Waives Five Days Clause When Musician Marries in Boston." The spouse was one William Dunbar, "a member of the theatrical profession." I don't know how long the union lasted, or whether or not it provided wedded bliss, but maybe it's not a good sign that Seydel registered a piece entitled "Dirge" for copyright a few months later. She never took his name professionally, at any rate.

In the late 1920's, Seydel served as concertmaster with the Boston Women's Symphony. She taught violin and solfeggi, possibly at the New England Conservatory, from 1920 to 1937, and is listed in a document of new Department of Music hires for Boston schools in 1946. It seems her concertizing reached at end sometime in the 1930's.

Besides the Bijou Minuet in Volume Two and the Minuet in Volume One, I looked at two other compositions by Seydel. Valley of Dreams and A Sunset Picture were both copyright in 1927, and are significant departures from the earlier minuets. Somewhat impressionistic in character, both were more dissonant and dreamy. I remember not liking either one very much, but now I wish I could to review them again and see I what I think.

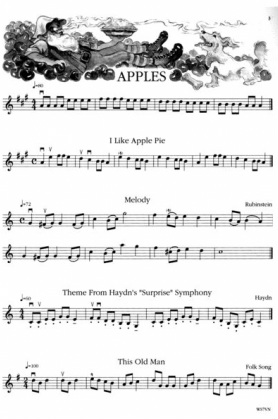

Bijou Minuet suited the need for a straightforward, entertaining piece in 1st and 3rd position. Of technical note is the bowing in the A section, which could be treated as either elementary upbow staccato/hooked bowing, or as "standing spiccato"-- upbow circle lifts that don't travel. The scalar motion in the outer sections lends itself very nicely to learning note/finger placement in 3rd position, in everyone'a favorite key of D major. The trio spices things up a bit with chromatic 16ths on many downbeats. I used the "modern" chromatic fingering rather than sliding fingers. In several spots, a shift is required from open A or E to the 3rd finger in 3rd position. Students can test their growing feel for the location of 3rd position with these "leaps of faith!" Alternations between forte and piano dynamics about every two measures provides great fodder for work on sound and bow control. For it's 48 measures, Seydel's Bijou Minuet supplies plenty of meaty technique to keep a student satisfied!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed